Botox Enforceable Guidelines – Don’t Panic, Adapt

New enforceable botox guidelines have been introduced for advertising and marketing. Here, our founder, Dr Tristan Mehta explains what you need to know and his thoughts on these changes…

What happened?

The aesthetics community has been shaken this month by a surprise enforcement notice from the Committee of Advertising Practice (CAP), which outlines new enforceable guidelines for advertising the Prescription-Only Medication (POM) Botulinum Toxin, coming into effect from January 31 20201.

The regulator will use new monitoring technology to automatically discover non-compliant ads and report them to Instagram.

CAP is also rolling out a targeted advertising campaign on Facebook to raise awareness of this issue. This is the furthest-reaching enforcement notice ever issued by CAP. It’s set to target over 130,000 of the wide-ranging businesses within the cosmetic services industry. They are working with Facebook.

Who are the CAP, ASA and MHRA?

The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) was established in 1962 as an industry watchdog to monitor and adjudicate on breaches for the British Code of Advertising Practice (CAP Code) with the primary objective of protecting the public from misleading, inaccurate or inappropriate advertising whether online, in print or in broadcast.

Any promotion of a POM to the public is a breach of the CAP Code, and an offence under the Human Medicines Regulations 2012.

CAP Code 12.12 states that “Prescription-only medicines or prescription-only medical treatments may not be advertised to the public”.

Importantly, this Code is not new – but the enforcement of it is.

The enforcement notice references CAP’s legal backstop should practitioners not comply. This is the Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). The MHRA is the executive agency of the Department of Health and Social Care in the United Kingdom which is responsible for ensuring that medicines and medical devices work and are acceptably safe.

Theoretically the practitioner’s Professional Statutory Regulatory Body (e.g. GMC, NMC, GDC) could be informed.

What about the JCCP – where do they come in?

The Joint Council for Cosmetic Practitioners (JCCP) was formally launched In February 2018 as a “self-regulating” body for the non-surgical aesthetics and hair restoration sector in the United Kingdom. It has achieved Professional Standards Authority (PSA) recognition and charitable status, and has received funding from the Department of Health and Social Care.

The charitable status reflects the overarching not-for-profit mission of the JCCP, which is to improve patient safety and public protection.

This is not the first time the JCCP and ASA have worked in partnership. Back in August 2019, the ASA investigated rogue aesthetic training companies based on complaints to the JCCP2.

The led to action on three culprits – companies with names such as “Boss Babes Uni” and “The Aesthetics Uni”.

The ASA is receptive to referrals from the JCCP3, and it appears this partnership is in full effect given the latest enforcement notice.

What exactly are the new enforceable guidelines?

The CAP guidance is clear: Practitioners cannot directly or indirectly reference botulinum toxin in marketing materials.

- Practitioners must remove all references to Botox and other brand names for botulinum toxin

- Practitioners must not indirectly reference the drug, for example by using phrases such ‘anti-wrinkle treatments’ or ‘wrinkle relaxers’

- Practitioners must avoid promoting the drug via describing medical conditions it can treat, such as hyperhidrosis

Instead, practitioners are recommended to advertise the consultation instead.

If the service being advertised is a consultation for the treatment of lines and wrinkles, this will likely be acceptable.

These guidelines don’t currently apply to dermal filler injectables.

Why is this important?

Instagram has become a major marketing channel for new aesthetics practitioners and existing practitioners alike.

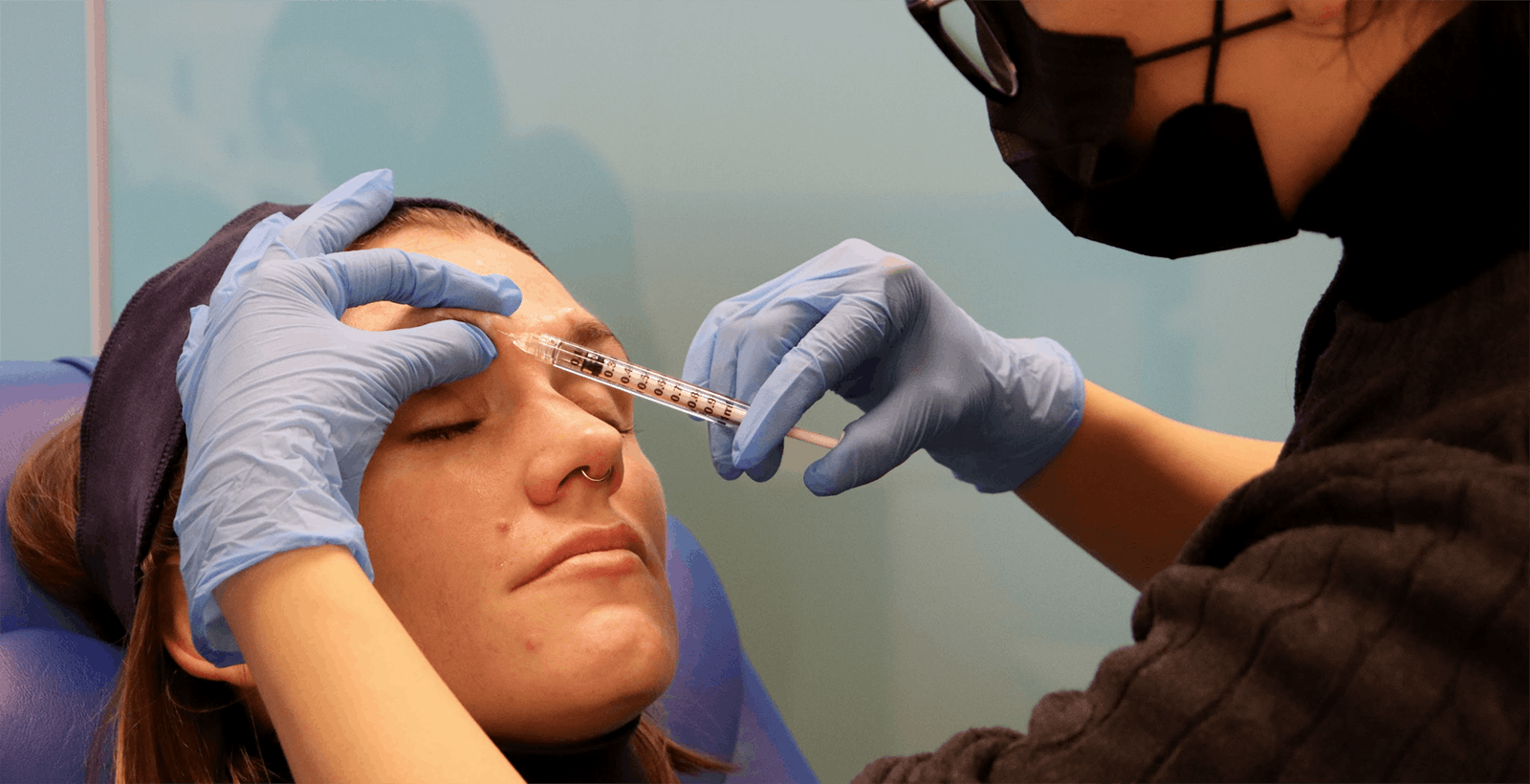

Growth in demand for injectables as been attributed to the rise of social media, compounded by influencer culture and reality TV. Because aesthetics is – by definition – represented visually, it lends itself well to Instagram marketing.

And therein lies the problem.

Social media is the most cost effective way for new practitioners to acquire patients, yet it’s fraught with ethical and regulatory challenges. These will now be enforceable from 31 January 2020.

From an ethical standpoint, practitioners must be careful not to minimise the risks involved in injectable interventions. They must also ensure they do not mislead the public in terms of what is achievable as a result.

Instagram has been further criticised as driving unhealthy body image standards and mental health distress. This is especially in relation to younger patients who may be more vulnerable to such marketing.

Why is it causing a stir?

Unquestionably, fillers are the more dangerous injectable treatment – which are still astonishingly unregulated.

Fillers are a gel which can impose mechanical complications such as vascular occlusion (and potentially tissue death), alongside acting as an implant which can become infected or form chronic inflammatory nodules.

Botulinum toxin carries risks, however these are largely limited to cosmetic asymmetry or unfortunate droops. There has been one reported case of anaphylaxis after a botulinum toxin treatment in 20174.

Many healthcare professionals are fed up of guidelines emerging which only exist to further restrict those who are already regulated by their professional statutory regulators. The Health Education England (HEE) guidelines5 recommended higher standards of qualification for injectors in 2016, and this guidance was inherited by the JCCP.

Medically qualified injectors who have achieved a Level 7 qualification in injectables can join the JCCP register – although this is still voluntary.

But there is still no recourse for the unregulated, non-medical practitioners who are offering injectable procedures.

Healthcare professionals may be concerned that this gives a commercial advantage to those who do not have as much to lose – who cannot be struck off or held accountable.

At the same time, we have been aware for many years of pre-existing guidelines from the ASA which give very clear recommendations for how (not) to advertise POMs. This is also supported in the GMC’s guidelines for cosmetic practice in April 20166.

So what should we do?

Educating thousands of healthcare professionals in injectables each year comes with some very clear responsibilities.

Being ethical is paramount. From the start, Harley Academy has embraced published guidelines from official sources – often when these are operationally extremely hard and costly to deliver, and when other training centres refuse to comply.

Healthcare professionals who choose to study with us expect that their investment will pay off and that they will be in good standing when regulatory changes are made, alongside being positioned as an expert in cosmetic injectables. And I would like to think that we succeed in achieving this.

The barrier to entry to offer injectables is very low. Anyone can complete a one day course, and begin promoting their treatments on instagram. When patients are exposed to poorly trained technicians offering treatments, the reputation for aesthetics declines as more complications and ‘botch jobs’ arise.

Enforcing better advertising protects the public from noise.

Good, safe practitioners will prevail. Those with longevity – who truly understand their field and are invested in lifelong studying within it – will continue to run the most successful clinics.

So here are my thoughts on how these enforceable guidelines affect the commercial prospects of our trainees and medical specialists within aesthetics:

- The single most important action to make your business succeed is simple: do a good job, consistently

- Word of mouth will always be the best marketing channel for your business

- Focus on retaining loyal clients, rather than attracting a transient database

- Social media for attracting patients is only one strategy for marketing

- If your entire aesthetics business relies upon promoting a POM on instagram, you aren’t in a good position

- If you have studied and trained properly, then let the world know – about the consultations and treatment plans you can offer, not the products!

- Most practitioners do not work as a specialist, they work as a technician. This represents this biggest gap in the market

- Practicing as a specialist transforms consultations from offering a transaction (e.g. lip filler, or 3 areas of toxin) to offering bespoke treatment plans which deliver far greater patient satisfaction – alongside greater revenue

- If you have ever been sick of seeing viral ‘instagram clinics’ which grasp the attention of thousands of followers, and want to see less of this, then consider these guidelines a good thing and a herald of hopefully tighter restrictions

Hearing that we must ethically advertise our products and services is nothing new – but enforcement is. And we should see enforcement as a good thing.

It means regulatory wheels are in motion. It could be the start of something really significant in legislation.

Practitioners will be forced to drive their business through the good old fashioned way of word of mouth and reputation. And social media can still be used to drive business in the right ways – but perhaps we all need some enforcement to set a good example, and drive up standards together.

With hope, it is only a matter of time before more statutory guidelines come into play – tackling some of the more crucial issues surrounding dermal fillers and restricting non-medical practitioners.

All information correct at the time of publication Article last fact-checked: 11 January 2023

References:

Enforcement Notice: Botox and other botulinum toxin products. Available at Asa.org.uk.

Jccp.org.uk. (2019). Joint Council for Cosmetic Practitioners (JCCP) complaints prompt Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) Investigation into Aesthetic Training Companies. Available at jccp.org.uk.

Asa.org.uk. (2019). Joint Statement: JCCP and the ASA. Available at Asa.org.uk.

Moon IJ, e. (2017). First case of anaphylaxis after botulinum toxin type A injection. – PubMed – NCBI. Available at Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Hee.nhs.uk. (2015). Report on implementation of qualification requirements for cosmetic procedures: Non-surgical cosmetic interventions and hair restoration surgery. Available at Hee.nhs.uk.

Gmc-uk.org. (2016). Available at Gmc-uk.org.

Download our full prospectus

Browse all our injectables, dermal fillers and cosmetic dermatology courses in one document

By submitting this form, you agree to receive marketing about our products, events, promotions and exclusive content. Consent is not a condition of purchase, and no purchase is necessary. Message frequency varies. View our Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions

Attend our FREE open evening

If you're not sure which course is right for you, let us help

Join us online or in-person at our free open evening to learn more

Our Partners

STAY INFORMED

Sign up to receive industry news, careers advice, special offers and information on Harley Academy courses and services